Economics is often referred to as “the dismal science”, a term coined by historian Thomas Carlyle in the mid-18th century when the discipline focused on the world’s limited resources and their inability to keep up with mankind’s growing needs. A lighthearted smear shared by bored or frustrated college students, this gloomy moniker now seems more fitting than amusing. As we fear ramifications of the worsening credit crunch, fret at declining home prices, and cringe at the pump, the most easily measurable impact that the troubled economy has brought to our personal fiscal health is evident in our financial statements. Whether an IRA, a firm sponsored 401k, or a taxable account, anything with stocks has declined with depressing regularity since last autumn.

Just as disconcerting, bonds have not served as a reliable respite in this bear market. Last quarter, 5-year treasury bonds produced a total return of minus 3.01% – worse than the Standard &Poor’s 500 drop of 2.73%. Accelerating inflation and deteriorating creditworthiness have shaken the normally steadfast fixed income arena. With inflation outpacing interest on cash instruments, what should you do? What should you be telling those clients who respect your views on such matters? For certain, you do not want to be, or sound like, a naive amateur panicking with the herd as it stampedes over a cliff. Wisdom and history suggest consistent participation as the best course.

Bad Times Past – and Maybe Passed

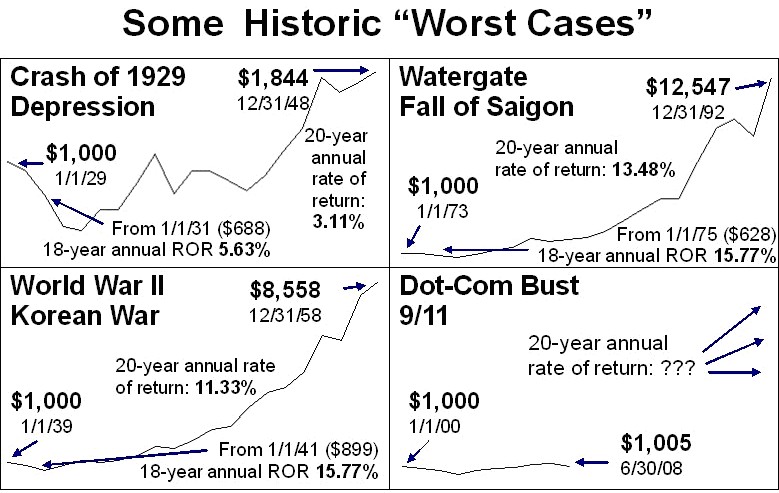

There is something narcissistic about each generation that sees things as not merely unique but also in the superlative extreme – the best of times, the worst of times, record setting, uncharted waters, etc. As bad as headlines may read, there have been a number of times when the market outlook was far worse than now. If one invested in the midst of these prior calamities, how did he or she fair thereafter?

While troubling events certainly had negative implications that damaged markets, the impact has always been temporary. Whether recovery took a year or a decade, recovery indeed occurred. Even if one had the misfortune of investing right before a precipitous drop, within 20 years – usually much sooner – rates of return were positive and higher than interest on cash. Further, if one invested after the shocks but still amidst troubling times, such as during the depression or wartime or the mid-70’s turmoil, eventual returns were even better and sometimes quite extraordinary.

At present, much of the bad news of the current cycle is behind us. This is not to suggest that we are at some sort of bottom and that stock prices will imminently spurt upward. But we have already adjusted expectations to the oil, real estate, and financial sector woes. It is not a stretch to believe that in a decade one will be happy for having maintained or even expanded stock holdings at this time.

Historic Perspective

Instead of focusing on those occasional troughs, it is instructive to look at an encompassing history of the market and simply recognize the extremes. Consider every possible 1-year, 5-year, 10-year, and 20-year investment horizon.

| Annualized Asset Group Returns: 1928-2007* | ||||

| Investment Horizon | 1 Year | 5 Years | 10 Years | 20 Years |

| Stocks Best | 53.99% | 28.56% | 20.06% | 17.88% |

| Worst | -43.34% | -12.47% | -0.89% | 3.11% |

| Average | 10.05% | 10.05% | 10.05% | 10.05% |

| Bonds Best | 30.71% | 19.80% | 13.80% | 11.07% |

| Worst | -2.66% | -0.37% | 0.78% | 1.64% |

| Average | 5.04% | 5.04% | 5.04% | 5.04% |

| Cash Best | 14.04% | 10.93% | 9.04% | 7.64% |

| Worst | 0.02% | 0.06% | 0.17% | 0.49% |

| Average | 3.77% | 3.77% | 3.77% | 3.77% |

Though any number of conclusions can be gleaned, note the following:

- Cash returns have never been negative for periods of 1 or more years

- Bond returns have never been negative for periods of 10 or more years

- Stock returns have never been negative for periods of 20 or more years

- Bonds have returned about 30% more than cash

- Stock returns have been about double that of bonds.

Basically, if your investment horizon is over 10 or 20 years and you are appropriately diversified, you need not worry about your assets frittering away due to today’s news. Assets may go down on any given day, month, or even year. But within a reasonable span, your portfolio value will have grown from where it is now. The greater your stock allocation, moreover, the higher your ultimate expected value.

Do NOT Try to Time the Bottom

The tendency to panic at the worst time is not new; nor is the rush to get into something well after hype has inflated prices. Numerous studies confirm the fact that mutual fund shareholders garner worse returns than the funds in which they invest. Often shares are bought at high prices after good news and advertised growth excite interest. Conversely, shares are frequently sold at low prices after discouraging news has already had its impact.

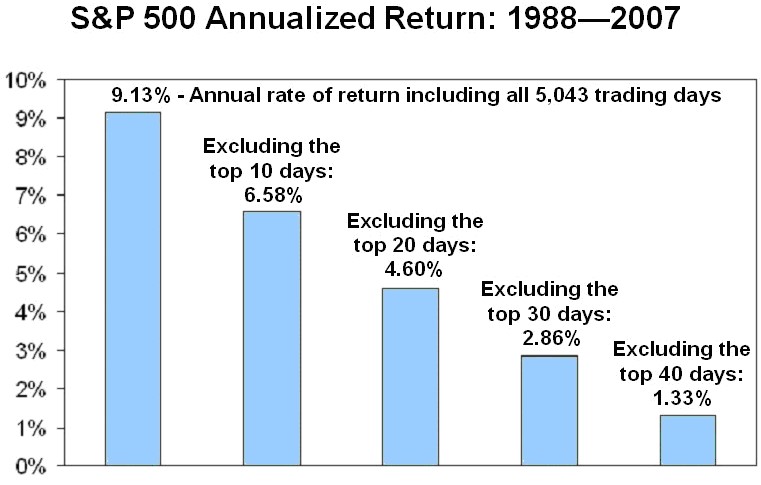

Statistically, there is a broader reason not to pull out or otherwise try to time the market. While stocks have provided the highest return over time versus bonds and cash, much of that extra return has occurred in large one-day spurts. Information flows rapidly. The catalysts of major market movements, such as Federal Reserve action or a political event, create instant reevaluations and sharp movements. Market reversals, from bear to bull and vice versa, are often sudden and intense.

To illustrate, if you invested in the S&P 500 for the 20 years 1988 through 2007, your assets would have grown at a compounded annual rate of 9.13%. If you missed only the best 30 days, out of a total of 5,043 trading days, your annual rate of return would have been 2.86%. It would be a shame to take on all the risk of the stock market and then under-perform bonds and cash simply by trying to guess market bottoms.

“Timeless” Advice

The notion of disciplined investing is not limited to weak markets. As demonstrated, maintaining or increasing stock positions when prices are low is a sound strategy. Equally sage, one should not become euphoric in strong markets. Many investors were burned in 2000 after jumping on the internet bandwagon in the late 1990’s. Other sectors such as oil in the 1980’s and real estate on multiple occasions harmed fad chasing investors in a like manner. Allocate your assets to stocks and bonds in an appropriate manner given your long term goals and tolerance for risk. Maintain this allocation in good times and bad – adding to that which has fallen and trimming that which has risen when imbalances become apparent.

Stated otherwise, when you shift investments, buy low and sell high. Don’t get suckered into doing the reverse.

This article was originally published in New Jersey Lawyer September 1, 2008.